Newtonian Physics Applied to Flight

In this part we introduce the the fundamental physical laws governing the forces acting on an airplane in flight, and what effect these natural laws and forces have on the performance characteristics of airplanes. To competently control the airplane, the pilot must understand the principles involved and learn to utilize or counteract these natural forces.

Modern airplanes, not only military airplanes, have what may be considered high performance characteristics. Therefore, it is increasingly necessary that pilots appreciate and understand the principles upon which the art of flying is based.

Dinamics of a Material Point

The basic laws of motion are applied to any moving, solid object. For the sake of simplicity, the moving object is idealized to be a concentrated mass $m$, i.e. a point, hence it has no physical dimensions. The motion of a point in a three-dimensional space is termed translation. Isaac Newton proposed the following three basic laws of motion in his revolutionary work dated 1687, titled Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (“Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy”):

-

A particle moving in a straight line at a constant speed $V$ will continue to do so unless a force $\mathbf{F}$ acts upon it.

-

The time rate of change of the velocity — i.e., the acceleration $\mathbf{a} = \mathrm{d} \mathbf{V}/\mathrm{d}t$ — of a particle is directly proportional to the force acting upon it. The constant of proportionality is the mass of the object — i.e. $\mathbf{F} = m \mathbf{a}$.

By defining the product of the mass of the particle with its velocity as its linear momentum $\mathbf{Q} = m \mathbf{V}$, it is implied that the time rate of change of the linear momentum vector is equal to the force applied to the particle \[ \mathbf{F} = \frac{\mathrm{d}\mathbf{Q}}{\mathrm{d}t} = \frac{\mathrm{d}\big( m \mathbf{V} \big)}{\mathrm{d}t} \label{eq:Newton:Second:Law} \]

-

If a particle exerts a force on another particle, the second particle simultaneously exerts a force equal in magnitude and opposite in direction on the first. The second force is called a reaction to the first force.

Newton’s laws are valid only for an inertial observer. Such an observer, by definition, must not be undergoing any acceleration; otherwise the velocity and acceleration measured by her would not satisfy Newton’s laws.

Newton’s first law of motion implies that the velocity of a moving particle is a vector $\mathbf{V}$ whose magnitude (speed $V = |\mathbf{V}|$) and direction (straight-line motion) remain constant with time, until and unless an external agency — force $\mathbf{F}$ in Eqn. (\ref{eq:Newton:Second:Law}) — acts upon it. This is the basic property (inertia) possessed by all objects having mass.

Many common flight situations involve a straight-line motion of the vehicle at a nearly constant speed — e.g., an airplane flying steadily and level or climbing at a constant rate, or a glider descending at a fixed glide angle. In such a flight, all the force vectors on the vehicle (regarded as a particle) must add to zero, otherwise, by the first law, either the speed or the direction of the vehicle will change with time.

The equilibrium condition where all the forces on a vehicle are balanced (i.e., sum to zero) is a natural atmospheric flight state, requiring the smallest energy expenditure for a given range. Observe that such an equilibrium state does not exist for space flight vehicles, which are always pulled toward the center of a massive body by gravity. Similarly, an airplane either taking-off, or performing maneuvers, has an accelerated flight condition where the forces are unbalanced.

The second law of motion tells us how a change in the velocity vector is produced when a force is applied. Suppose the force is applied only tangentially (that is, along the direction of motion). Then there cannot be any change in the direction of the motion, because the initial velocity and its change due to the applied force are both along the same straight line. This is a simple way of saying that the vectors \[ \mathbf{V} \,,\;\; \mathbf{F} \,,\;\; \mathbf{a} \,,\;\; \mathbf{a}\,\mathrm{d}t \label{eq:Vectors:Parallel} \] are all lined up. Hence, being the force $\mathbf{F}$ applied at a given time $t$, the velocity $\mathbf{V}(t)$ will change in a short amount of time $\mathrm{d}t$ and become \[ \mathbf{V}(t+\mathrm{d}t) = \mathbf{V}(t) + \mathbf{a} \, \mathrm{d}t \label{eq:Vectors:Parallel:B} \] a vector still parallel to the initial direction of motion.

Motion of a Material Point Along a Curved Path

Now, let us consider a case where the magnitude of the velocity is unchanged, but its direction is varied. This can happen if the force is applied to the object at a 90 degree angle (or normal) to the direction of initial motion. In such a case, there is no possibility of a change in the magnitude of the velocity vector (i.e., its speed), but only in its direction. This is the case where both the initial and the final velocity vectors have an equal length, but different directions. A flight example where the applied force is always normal to the direction of motion is that of a satellite in a circular orbit around a spherical planet. Here, the gravity is the only external force, and pulls the satellite toward the center of the planet, leaving the speed of the satellite constant with time.

Whenever the flight direction is changed without any change in the speed, a force must have been applied to the vehicle along the instantaneous radius of curvature of the flight path. Since such a force — called the centripetal force — acts in a direction perpendicular to the instantaneous flight direction, it is incapable of changing the speed.

The second law of motion encompasses the most general situation, namely when the force is applied to the object at an arbitrary angle to the direction of motion. The resulting change (i.e., acceleration) is then both in the magnitude (speed) and the direction of the velocity vector, and the object describes a curve with a varying speed. An example of such a motion is a roller-coaster ride, in which variations in both the speed and the direction occur at the same time. A general flight path through the air or space is similarly analyzed by Newton’s second law of motion.

The third law of motion allows us to easily understand the source of many forces, which would otherwise require a detailed mathematical analysis. A complex interplay of various mechanisms often boils down to a simple action–reaction pair of forces, to which the third law can be applied. For example, the creation of the aerodynamic lift in fixed-wing vehicle flight is often simply explained by recalling an action-reaction principle (impulsive theory of lift production). In formal textbooks on aerodynamics, the lift is explained by more complicated fluid mechanics principles. Similarly, the creation of the thrust by an aircraft or a rocket engine is directly explained by Newton’’’s third law.

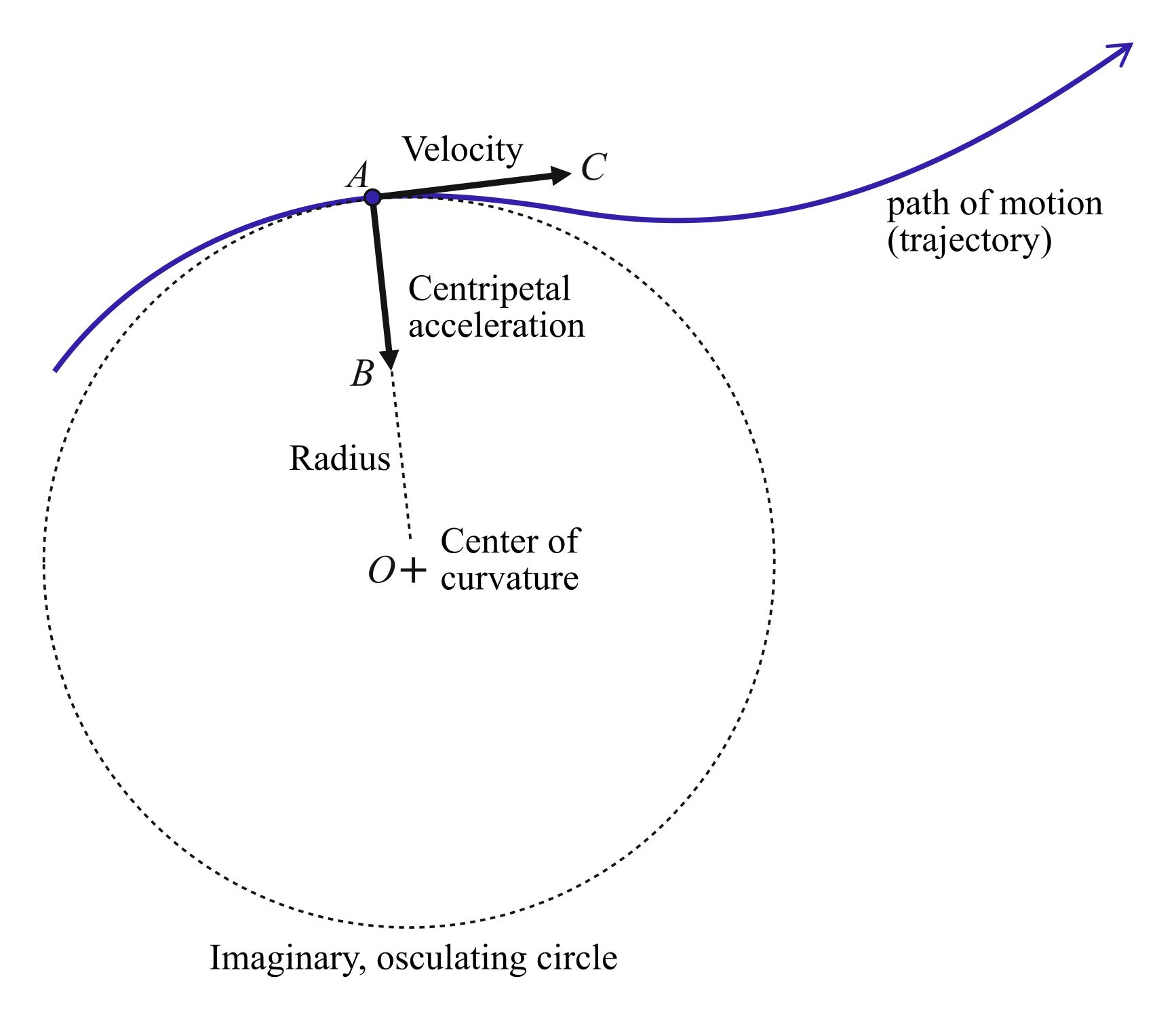

Now we are in a position to understand very broadly the difference between straight-line (rectilinear) motion and curved (curvilinear) motion. To summarize the earlier discussion, a force must be applied in order to cause a change in the velocity of a particle. If the direction of the applied force is along (or opposite) to the direction of motion, it can only cause a change in the speed of the particle, but not in its direction, hence the object continues to move in a straight line. Whenever a force is applied at an angle to the direction of initial motion, a change in the direction is always produced, resulting in a curved path. The essential nature of a general curvilinear motion is depicted in the above figure. At a given instantaneous position, $A$, along the trajectory of a particle, there exists a centripetal acceleration, $AB$, which acts toward the instantaneous center, $O$, of an imaginary circle. The imaginary circle is constructed such that a tangent to it at the point $A$ gives the instantaneous velocity vector, $AC$. The angle $\angle OAC$ is 90 degrees, implying that the centripetal acceleration acts normal to the flight path. The radius of curvature of the path at a given instant is the radius of the imaginary circle, which may keep on varying with time if there also exists a net force in the tangential direction (i.e., along the trajectory), causing a change in the speed of motion.

Let us consider the simplest case of curved motion, namely a particle moving in a circular path. In this special case, the force is applied continuously toward the center (i.e., in the centripetal direction) of a fixed circle traced by the point mass. If we break down the time into many infinitesimal intervals (or instants), then at each instant, it is as if the force is applied at a 90 degree angle (i.e., normal) to the instantaneous direction of motion. Consequently, there is no change in the speed of the object. However, the direction keeps on changing at every instant due to the normally applied force, and the result is a circular motion. The centripetal force must always act in order to maintain such a motion.

By the second law of motion, the magnitude of the force increases in proportion with the acceleration, that is, the time rate of change of velocity. In a circular motion, the acceleration is proportional to the square of the angular speed (revolutions per second). If $R$ is the circle radius, and $V$ is the constant speed along the circular path, the angular speed is \[ \omega = \frac{V}{R} \label{eq:Circular:Motion:Omega} \] and the centripetal acceleration is \[ a = \omega^2 R = \frac{V^2}{R} = V \omega \label{eq:Circular:Motion:Acceleration} \]

By the first law of motion, it is clear that the only time a particle experiences a force-free condition is when it is moving in a straight line at a constant speed (uniform rectilinear motion). In contrast, at every instant that a particle moves in a curve, its speed may (or may not) be constant, but the direction is instantaneously changing due to a normally applied centripetal force. However, it resists the curved motion by applying a normal force in the opposite direction. This is known as the centrifugal inertial force.

Here we are touching on an important but usually difficult to grasp principle. The way an object can be forced to move depends only upon the forces that can be applied to the object. A typical example in flight mechanics is that of an airplane in a turn, idealized as a point mass lumped in the vehicle’s center of gravity, following a circular and horizontal flight path. The speed of the object, as well as the rate of turn it is required to make determines the required acceleration, which must obey the second law of motion in terms of the available normal force. For a given flight speed, the smaller the radius of the required turn, the larger centripetal acceleration (hence normal force) is required. For a given radius of turn in a curve, a larger speed requires a proportionally larger centripetal acceleration, and thus a larger normal force. In flight, the normal force is usually supplied by the lift of the wings. If an aircraft is moved in a much tighter curve, or at a much higher speed than for which it is designed, then the lift produced by the wings can exceed their structural strength, causing them to disintegrate. On the other hand, a human pilot can “black-out” in a tight maneuver, where the normal acceleration is so high that the blood is prevented from circulating to the brain due to the limitation of the heart’s pumping capacity. Therefore, the acceleration limits of an airplane are usually placarded on the instrument panel in the cockpit, so that they are never exceeded for safety reasons.

Motion of a Solid Body

TBD.

Rotations

TBD.

Rapid roll

TBD.

Pull-up

TBD.

Turn

TBD.

Spin

TBD.