The Atmosphere

Humans live at the base of an invisible ocean of air, which is referred to as the atmosphere. The atmosphere is always in a state of physical change, giving rise to changing weather conditions on extremely vast scales. The pilot has to recognize the “mood” of the atmosphere before he decides to go up in the air. He can take the help of weathermen and forecasters to understand meteorological conditions, but the final go or no-go decision rests with the pilot.

The atmosphere is the gaseous medium enveloping our Earth and revolving with it as an integral body. The air is the basic gas composing the atmosphere, but to a very-small extent it also contains water vapor (the basic source of all fog, cloud, and precipitation) and suspended tiny microscopic solid particles called aerosols. The atmosphere gets lighter with increasing altitude. The atmosphere regulates heat, air, and moisture. It also protects us from the sun’s harmful rays and from meteoroids, and maintains the ecological balance on the Earth. Flying takes place only in the relatively denser portion of the atmosphere.

A pilot of an aircraft, however, is not interested in the details of the composition of the air. A pilot views or senses atmosphere from its impact on flight performance.

The Pilot’s View of the Atmosphere

A pilot generally finds the atmosphere quite friendly. It makes flying enjoyable to such an extent that he or she chooses flying as a career. The atmosphere exhibits its friendliness by giving sufficient “lift” to his aircraft. The atmospheric winds have inexhaustible energy that is utilized for windmills, generating electricity, cooling, and providing thrust and power to air-breathing engines.

The same atmosphere can sometimes be quite unfriendly too, and may even behave like an enemy. A pilot’s concern is that the atmosphere also has its own independent motion which sometimes dangerously interacts with the motion of the aircraft. A pilot knows by experience that air is made up of changing wind speeds and directions, turbulence, vertical air currents, updrafts and downdrafts, gusts, circulations and vortices, micro bursts, tornadoes, wind jets, and windshear. These may cause an aircraft to stall, roll, spin, yaw, sideslip, or engage in violent tossing that cannot be controlled. Atmospheric winds can uproot trees and houses, overthrow automobiles and railway carriages, and destroy bridges and tall buildings. For a pilot, water vapor causes fog, cloud, rain, snow, hail, thunder, lightning, rainbow, and halos. Many of these atmospheric phenomena put a pilot and his aircraft in difficult situations varying from discomfort to disaster. In certain catastrophes it becomes difficult to identify which is to blame — the pilot, the aircraft, or the atmosphere. This leads us to attempt to gain more knowledge of the atmosphere so that the pilot-aircraft-atmosphere system becomes more reliable.

Temperature, Pressure, and Density of the Atmosphere

Temperature, pressure, and density are the three characteristic quantities of the atmospheric air and it is important to know their behavior. They are not independent because they are related by the equation of state of the air modelled as a perfect gas.

Atmospheric Temperature

Temperature is the most significant quantity which influences pressure and density of the air. The differential heating on Earth causes weather changes.

Temperature and its significance to flying.

Air temperature is directly a measure of the average kinetic energy of air molecules. It is a physical quantity indicating the degree of heat or coldness of air.

For flying, it is important to know air temperature at the time of takeoff and landing, and during flight. The temperature and pressure fix the air density, which in tum fixes the airspeed of the aircraft. The temperature maps of the atmosphere include lines of freezing temperature so that the pilot realizes the chances of icing acting as a hazard to an aircraft. The difference between temperature and dew-point temperature of the atmosphere indicates the probability of fog formation. The changes in temperature alter the Reynolds number and Mach number of flight. The temperature appears directly at several places during the data reduction from flight tests.

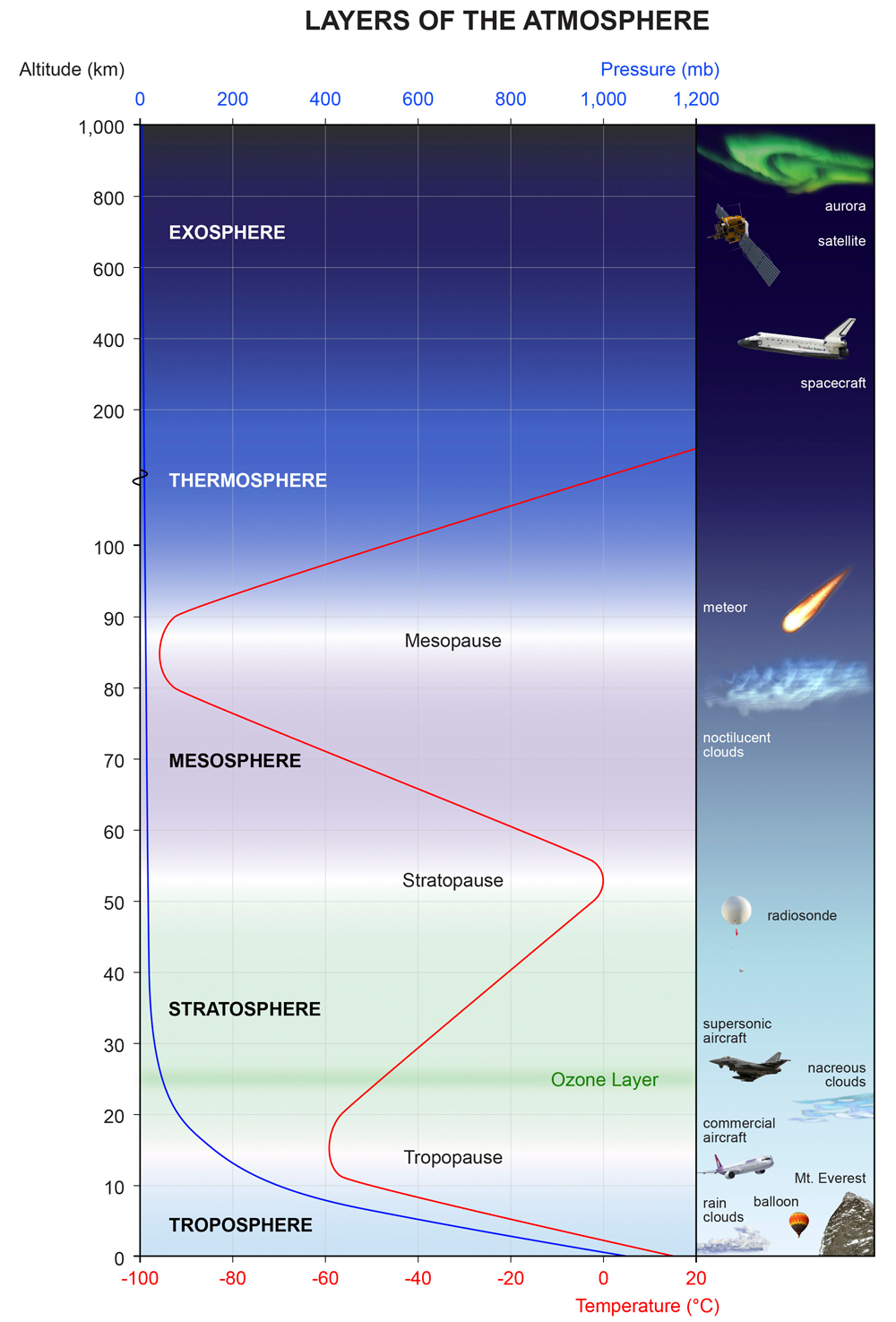

Typical mean temperature variation with altitude is shown in Figure above. The zigzag behavior of the curve appears puzzling at first sight. At any particular point in space, there are variations of temperature with time during a year. This variation is more near the Earth and in the troposphere, and it reduces as the altitude increases. The mean temperature decreases with altitude in the troposphere and again in the mesosphere.

The rate of change of temperature with height $h$ in the atmospheric layers at a place and time is called its temperature lapse rate or simply lapse rate, which is denoted by $\lambda$. The lapse rate is considered positive if the temperature decreases with height, and vice versa. \begin{equation} \lambda = - \frac{\mathrm{d}T}{\mathrm{d}h} \label{eq:Lapse:Rate} \end{equation}

The lapse rate is zero in isothermal layers. The lapse rate depends on whether the thermal process is adiabatic or nonadiabatic and on the moisture content in the atmosphere.

In the adiabatic process an air mass or air parcel (or any other gas) is compressed or expanded in volume without gaining or losing any heat to or from outside sources. The vertical motion of air parcels in the atmosphere is considered adiabatic because there is no heat exchange of heat energy from the external boundaries of the air parcel. In the rising currents, air expands and cools adiabatically. Similarly, in the descending layers, air is compressed and warms adiabatically.

The dry air adiabatic lapse rate (DALR) is 3 °C per 1000 ft (304.8 m), or 1 °C per 100 m. The saturated-air adiabatic lapse rate (SALR) is 1.5 °C per 1000 ft or 0.5 °C per 100 m. Therefore, $\lambda_\mathrm{SALR} = \frac{1}{2} \lambda_\mathrm{DALR}$.

Atmospheric Pressure

Knowledge of atmospheric pressure is important to pilots in determining altitude, understanding the functioning of altimeters, and forecasting the weather.

Pressure and its significance to flying.

The pressure at any point in the atmosphere is the weight of the air column, of unit cross-sectional area directly above it, up to the top of the atmosphere. It is also called barometric pressure because it is usually measured by a mercury barometer. In aviation meteorology, the pressure is commonly measured in inches or millimeters of mercury but expressed in millibars where, 1 mb = 100 N/m². In the SI systems, it is expressed as N/m². The sea level pressure in the atmosphere generally varies from 950 mb to 1050 mb. The standard atmosphere sea level pressure is 1013.25 mb, or 1.013·10⁵ N/m² at 15 °C of air temperature.

The winds move from the higher- to the lower-pressure side. The pressure distribution in the atmosphere controls the winds, which are of great importance to a pilot in planning cross-country flights. The aircraft altimeters are operated by atmospheric pressure and they must be properly set to obtain correct readings of altitude. Pressure maps are drawn at meteorological stations indicating isobars, high and low pressures, and pressure systems. These maps help to forecast weather to assist pilots.

The air pressure is maximum at sea level and decreases with the increase in altitude. A rule of thumb valid for the lower parts of the troposphere is that, for every increase of altitude of 27 ft (8.2 m) there will be drop in pressure of 1 mb. At altitudes of 5, 10, and 20 km the pressures are, respectively, about 1/2, 1/4, and 1/20 of the sea-level pressure. The pressure decreases less and less slowly with the increase in altitude. The pressure of cold and heavy air decreases more rapidly with altitude than that of warm and light air. The pressure maps are provided for different pressure altitudes because pressure systems change with altitude. That is, the isobar contours and the regions of high pressure/low pressure can be quite different at different altitudes.

Station pressure, sea-level pressure, and altimeter setting.

The station pressure is the reading of barometric pressure at the observing station. The higher the elevation (altitude) of the observing station, the lesser is the station pressure. To be consistent, each observing station translates its reading in terms of standard atmosphere sea level pressure which is usually reported in millibars. The altimeter reading corresponds to standard atmospheric pressure. At sea level, the altimeter reading differs slightly from the ambient sea level pressure because the standard sea level pressure corresponds to 15 °C. When correctly set, the altimeter then reads the true elevation of the airport at which the aircraft is parked. If the pilot does not know the altimeter setting but knows the elevation of the airport at which it is parked, he or she can enter the correct elevation on the dial and also get the correct altimeter setting. The altimeter setting is reported in inches of mercury (in.Hg).

Atmospheric Density

Air density is an invisible physical quantity that cannot be directly sensed by a human body. It is, however, a most important quantity in aircraft performance.

Density and its significance to flying.

The density of atmospheric air at any given point is known as its mass per unit volume. Atmospheric air density is directly proportional to pressure and inversely proportional to absolute temperature. In the lower parts of the troposphere a 3 °C rise in temperature corresponds to a 1% decrease in density, and vice versa. The density of standard atmosphere at sea level is 1.225 kg/m³ or 0.002377 slug/ft³.

Atmospheric density decreases with increase in altitude, and its decrease is faster near the Earth than at higher altitudes. This is because, the air being compressible, more air mass is confined near the Earth’s surface. At the altitudes of 5, 10, and 20 km the air density is about 60%, 35%, and 7%, respectively, of its value at sea level. The lines of constant density shown in a meteorological map are called isosterics.

Aircraft performance, engine thrust or power output, and airspeed indicator readings are affected by the density of air. Aerodynamic forces are directly proportional to the density of the air. A given aircraft needs to fly faster to maintain a given altitude if the air density decreases. In fact, every aspect of aircraft operation — takeoff, climb, cruise, turn, descent, and landing — depends on the density of the air through which the aircraft is moving. Aircraft maneuvering limitations and ceiling also depend on air density. Propeller blades will produce less thrust in air of reduced density. Lower air density means a reduction in engine thrust, coincident with the need for higher takeoff and landing airspeeds, requiring a longer takeoff run. Alternatively, if a limited length of takeoff run is available, a lower density may necessitate a reduction in payload to meet the takeoff performance requirement.

There is no instrument on the flight deck panel that directly indicates the density of the atmosphere through which the aircraft is flying. The density can, however, be calculated after obtaining the measurements of the temperature and pressure of the atmosphere. The hazard of low air density must be guarded against, especially at unfamiliar airfields, at high altitudes, on hot days. The problem is further accentuated if the day is also humid, because humidity reduces the density of dry air.